Introduction to RNA Folding

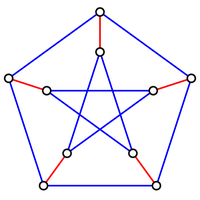

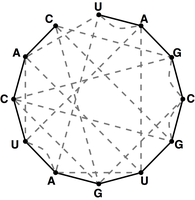

Figure 1. A hairpin loop is formed when consecutive elements from two different regions of an RNA molecule base pair. (Courtesy: Sakurambo, Wikimedia Commons User)

Because RNA is single-stranded, you may have wondered if the cytosine and guanine

bases bond to each other like in DNA. The answer is yes, as do adenine and uracil,

and the resulting base pairs define the secondary structure

of the RNA molecule; recall that its primary structure

is just the order of its bases.

In the greater three-dimensional world, the base pairing interactions of an RNA molecule

cause it to twist around on itself in a process called RNA folding. When two complementary intervals of bases

located close to each other on the strand bond to each other,

they form a structure called a hairpin loop (or stem loop), shown in

Figure 1.

The same RNA molecule may base pair differently at different points in time, thus

adopting many different secondary structures. Our eventual goal is to classify which of these

structures are practically feasible, and which are not. To this end, we will ask natural

combinatorial questions about the number of possible different RNA secondary structures.

In this problem, we will first consider the (impractical) simplified case in which every nucleotide forms

part of a base pair in the RNA molecule.

Problem

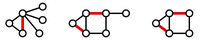

Figure 2. Three matchings (highlighted in red) shown in three different graphs.

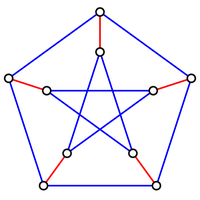

Figure 3. A graph containing 10 nodes; the five edges forming a perfect matching on these nodes are highlighted in red.

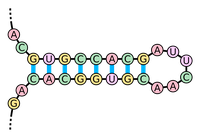

Figure 4. The bonding graph for the RNA string s = UAGCGUGAUCAC.

Figure 5. A perfect matching on the basepair edges is highlighted in red and represents a candidate secondary structure for the RNA strand.

A matching in a graph $\mathrm{G}$ is a collection of edges of $\mathrm{G}$

for which no node belongs to more than one edge in the collection.

See Figure 2

for examples of matchings.

If $G$ contains an even number of nodes (say $2n$), then a matching on $G$ is perfect

if it contains $n$ edges, which is clearly the maximum possible. An example of a graph

containing a perfect matching is shown in Figure 3.

First, let $K_n$ denote the complete graph on $2n$ labeled nodes, in which every node is connected

to every other node with an edge, and let $p_n$ denote the total number of perfect matchings in $K_n$.

For a given node $x$, there are $2n - 1$ ways to join $x$ to the other nodes in the graph, after which point we must

form a perfect matching on the remaining $2n - 2$ nodes. This reasoning provides us with the

recurrence relation $p_n = (2n - 1)\cdot p_{n-1}$; using the fact that $p_1$ is 1,

this recurrence relation implies the closed equation $p_n = (2n - 1)(2n - 3)(2n - 5)\cdots (3)(1)$.

Given an RNA string $s = s_1 \ldots s_n$, a bonding graph for $s$ is formed as follows.

First, assign each symbol of $s$ to a node, and arrange these nodes in order around a circle,

connecting them with edges called adjacency edges.

Second, form all possible edges {A, U} and {C, G}, called basepair edges; we will represent

basepair edges with dashed edges, as illustrated by the bonding graph in Figure 4.

Note that a matching contained in the basepair edges will represent one possibility for base pairing interactions in $s$,

as shown in Figure 5.

For such a matching to exist, $s$ must have the same number of occurrences of 'A' as 'U' and the same number of occurrences of 'C' as 'G'.

Given: An RNA string $s$ of length at most 80 bp having the same number of occurrences of 'A' as 'U' and the same number

of occurrences of 'C' as 'G'.

Return: The total possible number of perfect matchings of basepair edges in the bonding graph of $s$.

Sample Dataset

Sample Output