Dec. 4, 2012, 7:03 a.m. by Rosalind Team

Topics: Heredity, Probability

Mendel's Second Law

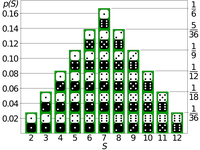

Figure 1. Mendel's second law dictates that every one of the 16 possible assignments of parental alleles is equally likely. The Punnett square for two factors therefore places each of these assignments in a cell of a 4 X 4 table. The probability of an offspring's genome is equal to the number of times it appears in the table, divided by 16.Recall that Mendel's first law states that for any factor, an individual randomly assigns one of its two alleles to its offspring. Yet this law does not state anything regarding the relationship with which alleles for different factors will be inherited.

After recording the results of crossing thousands of pea plants for seven years, Mendel surmised that alleles for different factors are inherited with no dependence on each other. This statement has become his second law, also known as the law of independent assortment.

What does it mean for factors to be "assorted independently?" If we cross two organisms, then a shortened form of independent assortment states that if we look only at organisms having the same alleles for one factor, then the inheritance of another factor should not change.

For example, Mendel's first law states that if we cross two

$\textrm{Aa}$ organisms, then 1/4 of their offspring will be$\textrm{aa}$ , 1/4 will be$\textrm{AA}$ , and 1/2 will be$\textrm{Aa}$ . Now, say that we cross plants that are both heterozygous for two factors, so that both of their genotypes may be written as$\textrm{Aa Bb}$ . Next, examine only$\textrm{Bb}$ offspring: Mendel's second law states that the same proportions of$\textrm{AA}$ ,$\textrm{Aa}$ , and$\textrm{aa}$ individuals will be observed in these offspring. The same fact holds for$\textrm{BB}$ and$\textrm{bb}$ offspring.As a result, independence will allow us to say that the probability of an

$\textrm{aa BB}$ offspring is simply equal to the probability of an$\textrm{aa}$ offspring times the probability of a$\textrm{BB}$ organism, i.e., 1/16.Because of independence, we can also extend the idea of Punnett squares to multiple factors, as shown in Figure 1. We now wish to quantify Mendel's notion of independence using probability.

Two events

More generally, random variables

As an example of how helpful independence can be for calculating probabilities, let

Given: Two positive integers

Return: The probability that at least

2 1

0.684

An Example of Dependent Random Variables

Figure 3. The probability of any outcome (leaf) in a probability tree diagram is given by the product of probabilities from the start of the tree to the outcome. For example, the probability that X is blue and Y is red is equal to (2/5)(1/4), or 1/10.Two random variables are dependent if they are not independent. For an example of dependent random variables, recall our example in “Mendel's First Law” of drawing two balls from a bag containing 3 red balls and 2 blue balls. If

$X$ represents the color of the first ball drawn and$Y$ is the color of the second ball drawn (without replacement), then let$A$ be the event "$X$ is red" and$B$ be the event$Y$ is blue. In this case, the probability tree diagram illustrated in Figure 3 demonstrates that$\mathrm{Pr}(A \textrm{ and } B) = \frac{3}{10}$ . Yet we can also see that$\mathrm{Pr}(A) = \frac{3}{5}$ and$\mathrm{Pr}(B) = \frac{3}{10} + \frac{1}{10} = \frac{2}{5}$ . We can now see that$\mathrm{Pr}(A \textrm{ and } B) \neq \mathrm{Pr}(A) \times \mathrm{Pr}(B)$ .